December 2006 NewsletterOn the Transportation of Material Goods |

|

| Figure 1. In situ photograph, Burial 72, Newton plantation cemetery, Barbados; metal bracelets can be seen on each arm. For details on these bracelets, see Handler 1997; for enlarged photos of each, see http://hitchcock.itc.virginia.edu/Slavery. Newton.. |

Quite naturally interpretations are considerably enhanced by the availability of ethnohistorical or ethnographic data (cf. DeCorse 1999), but the precise function of beads in African descendant sites, particularly small numbers scattered about, cannot be determined in many cases (beads are usually interpreted as parts of clothing or body adornment or much more vaguely as having some "ritualistic" function). In any event, in many cases beads offer material examples that reflect behavior arguably influenced by African practices and traditions.

|

| Figure 2. Components of necklace found with Burial 72, Newton plantation cemetery, Barbados. Dog teeth, fish vertebrae, money cowry shells, European glass beads and, in the center, a carnelian bead whose origin was undoubtedly Cambay, India. For details on these components, see Handler 1997. |

|

| Figure 3. In situ photograph of bead strand around pelvic area of Burial 340, New York African Burial Ground. See General Services Administration, 2006: vol. 1, chapter 5 (p. 153, Fig. 5.17) and vol. 3, Burial 340. |

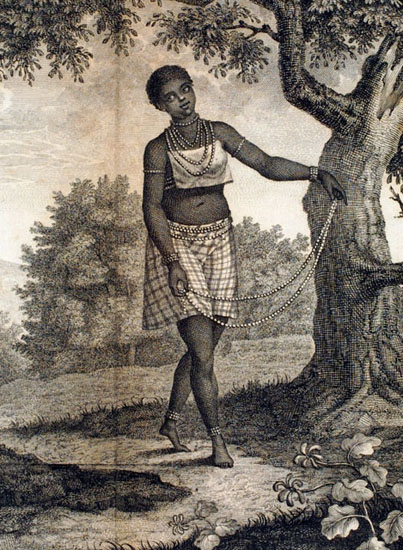

As is well known, beads were widely used by Africans during the era of the transatlantic slave trade. First-hand accounts of this period that offer information on African customs, material culture, and social behavior regularly mention beads, even though detailed descriptions of bead types and usages are usually absent. Africans themselves manufactured beads from a variety of materials, and glass beads of European manufacture were one of a number of trade goods Europeans commonly used along the West African coasts (e.g., Alpern 1995). Beads played a wide variety of roles in West African societies, including the purely ornamental in jewelry, clothing, or hair styling; as symbols or signifiers of social status and power; in ritualistic and spiritual dimensions of life, including their use as grave goods or as amulets for protection against misfortune or illness (Fig. 4; see, for example, DeCorse 1989; Stine et al. 1996:53-56; Handler 1997; Ogundiran 2002; DeCorse et al. 2003; Bianco et al. 2006 [and sources cited in these publications]).

|

| Figure 4. Angolan woman, showing clothing style and bead jewelry, 1786-87; based on a drawing made from life by a French naval officer. For details, see http://hitchcock.itc.virginia.edu/Slavery, Image Reference LCP-08. |

Given the widespread presence of beads among populations from which captives were taken to the New World, what chances or opportunities did these Africans have to retain their beads (or jewelry of any kind) and transport them across the Atlantic? This question is difficult to answer with certainty, although the answer has some bearing on archaeological finds in New World sites.[6] I have examined dozens of primary published accounts that touch in one way or another on the Atlantic slave trade, particularly, but not exclusively, that of the British. Most of these accounts provide no information on the questions I address here, but available information leads me to conclude that there would not have been a very great chance of retention in the vast majority of cases, considering the many thousands of voyages and the enormous numbers of people shipped by slavers over the several centuries of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. For one, there are indications that captive Africans were stripped of their jewelry as well as clothing (which could include elaborate robes or gowns made from woven fabrics, sarongs, skirts, and loin cloths of various styles and materials, depending on the cultural area and socioeconomic level of the captive) (Fig. 5) not long after their capture or during their treks overland in coffles and/or riverine transport from the interior to the coast; these trips could sometimes last for months, take place over many miles, and involve any number of middlemen (non-European) slave traders. If not completely denuded of clothing (and personal jewelry) during their transportation to coastal embarkation points, when they were loaded (or just prior to being loaded) on European slaving vessels, the evidence indicates their clothing was removed and that the transatlantic crossing was usually made in a state of nudity, or, at most, in ragged or tattered loin cloths (Fig. 6).[7] In what follows, I give examples of the evidence from primary sources. It bears stressing that although this evidence is widely scattered among the sources, is never detailed, and is usually quite fragmentary, it does provide a more or less consistent picture. Although the removal of beads (or metal or other jewelry) is not specifically mentioned in any of the sources, given the cultural value of beads in Western Africa, it might be conjectured that in most cases captors would have taken them from their captives even prior to the latter's sale to Europeans and their placement aboard the slave ships.

|

| Figure 5. Wolof Queen Ndeté-Yalla, Senegal, showing her robes and bead jewelry, 1850s; based on a drawing made from life by a Senegalese Catholic priest. For details, see http://hitchcock.itc.virginia.edu/Slavery, Image Reference Boilat03. |

Captured Africans reporting on their experiences offer several examples. Abu Bakr (Abubakr al-Siddiq), a Mande speaker from Jenne in present-day Mali, was captured in warfare around 1805 and "on that very day they made me a captive," he reported, "they tore off my clothes [and] bound me with ropes" (Wilkes 1967: 162). Venture Smith, captured as a child in the 1730s, was forced onto several coffles as he made the arduous trek from his homeland to the coast. As his captors/purchasers took new prisoners, he recalled many years later, "all their valuable effects were taken from them" (Smith 1798:12-13; cf. Handler 2002: 46-47). Ali Eisami, from the empire of Bornu in what is today northern Nigeria, was captured and sold as a slave to Europeans in 1818. At the coast he was put on a "small canoe" and transferred to the waiting slave ship. On board, "they took away all the small pieces of cloth which were on our bodies, and threw them into the water" (Smith et al. 1967: 213). And Mahommah Baquaqua was captured and shipped across the Atlantic to Brazil around 1845, presumably in a Portuguese or Brazilian slaving vessel. Upon being loaded on the ship, his vivid account reports, "we were thrust into the hold of the vessel in a state of nudity, the males being crammed on one side and the females on the other" (Law and Lovejoy 2001: 40-41, 153).

|

| Figure 6. An engraving based on an eyewitness sketch by a British naval doctor, Sierra Leone, 1805. Captioned, "Slaves: Shewing the method of chaining them." For details, see http://hitchcock.itc.virginia.edu/Slavery, Image Reference Spil04. |

Examples from Europeans are more numerous. In the late 17th century Willem [William] Bosman, an official of the Dutch West India company and chief factor at Elmina on the Gold Coast, noted that before enslaved Africans were loaded onto the slave ships "their masters strip them of all they have on their backs, so that they come aboard stark naked, as well women as men" (Bosman 1721:341).[8] Jonathan Atkins, on a slaving voyage in 1721, reported on the "great number of slaves . . . brought down to Whydah [Ouidah] and sold to the Europeans naked; the Arse-clouts they had . . . having been the plunder of the populace" (Atkins 1735: 111). A British Navy carpenter, James Towne, spent several months on shore during several trips to West Africa in the 1760s; he learned that when captured inland, the captives were "stripped naked and bound, if men"; women were treated the same, but not bound on their trek to the coast (in Lambert 1975b: 17). Reporting on his return to Jamaica from England aboard a slaving vessel in 1801, a Jamaican creole recorded in his journal that "none of the slaves had any clothing allowed them, and they all slept on the bare boards"; elsewhere he wrote the slaves were "extended naked on the bare boards [of the ship's decks] fettered with irons" (Riland 1827: 56, 57) (Fig. 7). In 1827, Théophile/Théophilus Conneau (Theodore Canot), a slave trader who had lived for many years on the West coast of Africa, recorded in his journal that captive Africans were taken to the shore and placed in canoes which took them to the waiting slave ship: "Once alongside [the ship], their clothes are taken off and they are shipped on board in perfect nakedness; this is done without distinction of sex. . . . the females part with reluctance with the only trifling rag that covers their Black modesty. . . . they are kept in total nudity the whole voyage" (Conneau 1976: 82; cf. Mouser 1979; Jones 1981).

|

| Figure 7. A French slaving vessel in the early nineteenth century showing how enslaved Africans were packed into its decks. A description of conditions aboard the ship, wherein the slaves "lay nude on planks," is given in manuscript on the left; for details, see note 9. |

A report of slaving activities on the African coast was given to the St. Helena Gazette in 1848. This tiny British colony in the South Atlantic had become a depot for illegal slaving ships captured by the British navy; by this date, about four decades after the British had abolished the slave trade, these captured ships presumably were not British. Enslaved Africans were taken from their holding areas on the coast to the beach, and before being placed on canoes that transported them to the waiting slave ship, "the little piece of cotton cloth tied round the loins of the slave is stripped off" (quoted in Jackson 1905:259). Jean Barbot, the agent for the French Royal African Company in the late 17th century, reported on a slaving voyage in 1698-99. Between meals men were occasionally given "short pipes and tobacco . . . and to the women, a piece of coarse cloth to cover them, and the same to many of the men" (Barbot 1732:547). Paul Erdmann Isert, a Brandenburger, was chief surgeon to Danish properties on the West African coast for about three years. In a letter written in 1787, he reported on the propensity of Africans to escape or commit suicide, and noted "For this reason on the French ships they are not even allowed a narrow strip of loincloth for fear they will hang themselves by it, which has in fact happened" (Winsnes 1992: 176).[9] As a final example from the primary sources, William Littleton, a British slaving captain who traded for about 11 years in the 1760s and 1770s, responded to a Parliamentary query concerning clothing afforded slaves during the Middle Passage; he reported "we do not allow them cloaths [sic] -- we could not keep them clean or preserve their health if they had cloaths [sic]" (in Lambert 1975a: 219-220). Other first-hand accounts provide similar, albeit usually very perfunctory, information (e.g., Duncan 1847; 1: 143; Beecham 1841: 354; Hawkins 1797:92-93; Newton 1788: 105; Robinson 1867: 78; Hurston 1927: 657; Thorp 1988: 447).

Perhaps, in some cases persons who wore beads (and metal jewelry considered of little value) were permitted to carry them to the Americas. This may have been the case, for example, with the very unique necklace discovered at Newton cemetery in Barbados or even the strand of waist beads found with a woman in the New York African Burial Ground (see above). Other small jewelry objects may have been smuggled aboard the ships by their captive owners and escaped detection by crewmembers; admittedly, however, there is no available data that even suggests that this might have occasionally occurred. However, some of the beads discovered in New World sites might have been acquired aboard the slaving ships themselves. There is evidence, from the British slave trade at least, that beads were occasionally distributed to enslaved Africans during the Middle Passage. This evidence is limited; thus it is impossible to even guess the frequency of this practice in the mid to late eighteenth century (evidence from earlier periods is lacking). In one of the better-known accounts of the Atlantic slave trade, Alexander Falconbridge, a surgeon aboard British slaving vessels in the 1780s, reported that during the Middle Passage "the women are furnished with beads for the purpose of affording them some diversion" (1788 [2000]: 210). The Jamaican creole referred to above, who traveled back to Jamaica aboard a slave ship, felt that the vessel's captain tried "to make the situation of the slaves comfortable"; the captain only resorted to "harsh measures," the Jamaican reported, when "entreaty and example had failed; and even then he used the cat [-of-nine-tails] sparingly, choosing rather to tempt them with a display of beads, etc.; which, with the women and girls, was sometimes effectual . . . . " (Riland 1827:58-59).[10]

In the British government's major inquiry into the slave trade in the late eighteenth century, a number of witnesses with first hand experience of slaving activities and the Middle Passage testified to Parliamentary committees. Among these witnesses, I discovered only two who mention beads. James Penny was a slave ship captain who made eleven voyages to the West Indies and North America in the 1770s and 1780s. He provided a detailed description of conditions aboard the ships, and, among other comments, noted that after meal times, captives were given pipes and tobacco, allowed musical instruments, and "the women are supplied with beads, which they make into ornaments." Robert Norris captained slave ships on five voyages in the late 1760s and during the 1770s. In an independent testimony he also reported that between meals the slaves were "supplied with the means of amusing themselves"; this included distributions of pipes and tobacco[11] for the men, while "the women and girls . . . amuse themselves with arranging fanciful ornaments for their persons with beads, which they are plentifully supplied with" (Great Britain, Board of Trade 1789; also, Lambert 1975c).[12] Quite independently of these Parliamentary witnesses, the primary sources from Barbados yield several cases. A British naval chaplain observed a slave sale on the island in early 1794 and reported that some of the Africans "were decorated with beads, given to them by their captors, and bracelets round their wrists and ankles" (Willyams 1796: 12-13). A few years later, a British army general visited a recently arrived slaving vessel in Barbados; he observed that the "females had all a number of different coloured glass beads hung around their necks" (Jeffery 1907; 1: 93-94).[13] Although I have not extensively explored the literature for other slaving ports in British America or the Caribbean, it is quite possible that similar information will be found in documentary sources for these areas.

Whatever the case, present evidence, despite its very fragmentary nature, suggests that the vast majority of beads recovered from New World diasporic sites were not in the possession of African captives when they boarded the slave ships in Africa. Rather, some of the beads found in these sites were acquired during the Middle Passage; others were acquired in the New World itself through internal markets or by other means, possibly including the plantation "reward-incentive" system (cf. Handler and Lange 1978: passim).

Notes[1]. The author is a Senior Fellow at the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities in Charlottesville. Neil Norman, Christopher DeCorse, and Chris Fennell provided welcome comments on earlier drafts.

[2]. Jane Webster has also raised this question and her intensive and long-term study of "the material culture of the Middle Passage" might ultimately provide a more definitive answer; for the time being, however, the question remains open (Webster 2005).

[3]. Several metal objects discovered at Newton cemetery in Barbados have a general African styling and reflect African methods of manufacture (particularly three bracelets and a copper ring associated with one of the burials); they may have been manufactured in Africa. Although a number of metal artifacts of personal adornment were discovered at the African Burial Ground in New York City, neither these nor those found at other North American sites appear to have originated in Africa (Handler 1997: 105-106, 107. 111-112; Handler and Lange 1978: 153-158; Bianco et al 2006; cf. Singleton 1991).

[4]. This carnelian bead, and a similar one, both originating in Cambay, Western India, will be discussed in a later issue of this Newsletter.

[5]. The money cowry (Cyprea moneta) with a broad habitat range in the Indian and Pacific oceans was a ubiquitous feature of the Atlantic slave trade and greatly valued by West Africans. Although I have been unable to conduct an extensive survey of African descendant sites which have yielded cowries, my impression is that only a handful of money cowries had been recovered from New World sites and most of these have been found singly and not as part of larger bead units such as necklaces or bracelets (e.g., Singleton 1991: 157, 188 n.9; Yakubik and Mendez n.d.; Gordon et al 2001; Brown 2006). There are, however, two major exceptions: Seven money cowries were recovered at Newton cemetery in Barbados in the early 1970s, and all of these were found in one necklace; and as a matter of coincidence(?), all of the seven cowries recovered from the African Burial Ground in New York City were also found with one burial, on the strand of hip beads (Handler and Lange 1978: 125-130; Bianco et al 2006:387). It is most likely that all of the New World cowries arrived via the Middle Passage, but it is impossible to determine if they were worn by the enslaved when they were captured.

A few finger rings of wood and bone/horn have also been found in North American sites; these also are possibly of African origin (Singleton 1991: 158, 188 nn. 11, 12).

[6]. The authors of the bead section in the final report of New York City's African burial ground essentially raise the same question, viz. "The presence in colonial Manhattan of glass beads characteristic of West African manufacture calls attention to the movement of adornment from Africa to the Americas. This aspect of the material culture of Atlantic slavery is not well charted. Some Africans arrived in the Americas with adornment, but how often this occurred and whether the items were brought from home or acquired en route is unclear" (Bianco et al. 2006: 395-396).

[7]. Describing the Portuguese slave trade in Central Africa, Miller's detailed and vivid description from primary sources of the coffles and barracoons reports that captives held in the "filthy and unhealthful" coastal barracoons received "no clothing" and those taken from the barracoons to the embarkation points were "dressed in loincloths (tangas) or crude camisoles made . . . of burlap wrappings recovered from the bundles and bales of imported goods"; but on the ships, the slaves, reported one primary source, were "almost naked" (Miller 1988: 398, 402-403 n.92).

[8]. Bosman's account was first published in Dutch in 1703, and the first English translation was published in 1705. Van Dantzig (1975) has systematically compared the latter and the former in a series of articles in History in Africa (spread over volumes 2 to 11) and seems to raise no objection to how the above quotation was translated.

[9]. An apparent eye-witness account of conditions aboard French slaving vessels in the early nineteenth century vividly describes the cramped conditions on board and reported how on the decks, "the enslaved lay nude on planks, without being able to change their position" [". . . ils sont couchés nus sur les planches, sans pouvoir changer de position"] (Societe de la Moral Chretienne 1826, my translation; for this account, see the website The Atlantic Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Americas (http://hitchcock.itc.virginia.edu/Slavery), Image Reference JCB_01203-5). Robert Harms suggests that slaves were "naked" on board the Diligent, a French slaving vessel in 1731-32, and that they came aboard the ship in that condition (Harms 2002: 297, 312).

[10]. Over 11,000 beads were recovered from the wreck of the slave ship Henrietta Marie, which sunk near the Florida Keys in 1700; it was making its return voyage to England after selling its contingent of slaves in Jamaica (David Moore, pers. comm., 1 Dec. 2006; cf. Moore 1997: App. F, note 1). The beads were undoubtedly the residues of trade goods used in West Africa, but some may have been distributed to slaves during the Middle Passage.

[11]. The distribution of pipes and tobacco, particularly to men after the main meal of the day, was apparently a fairly regular occurrence on British slaving vessels, perhaps on the French as well (Barbot 1732: 547; see above), by the latter half of the eighteenth century. There are no data on whether the enslaved were allowed to keep the pipes.

[12]. In another published version of his testimony, Norris merely says, "the women are supplied with beads to ornament themselves with" (in Lambert 1975a: 3-4).

[13]. On the Mattaponi river in Virginia in 1732, a visiting Englishman observed a recently arrived slave ship: "The boyes and girles [were] all stark naked; so were the greatest part of the men and women. Some had beads about their necks, arms, and wasts [sic], and a ragg or piece of leather the bigness of a figg leafe." Whether the beads were acquired on board the ship or belonged to the captives before they left Africa is not given. Whatever the case, the Englishman's host purchased 8 men and 2 women "and brought them on shoar with us, all stark naked" (Stiverson and Butler 1977: 31-32).

References

Alpern, Stanley B. 1995.

What Africans Got for their Slaves: A Master list of European Trade Goods. History in Africa 22: 5-43.

Armstrong, D. V. 1990.

The old village and the great house: an archaeological and historical examination of Drax Hall Plantation, St. Ann's Bay, Jamaica. University of Illinois Press.

Atkins, J. 1735.

A voyage to Guinea, Brazil and the West Indies in His Majesty's ships, the "Swallow" and "Weymouth." London (reprinted, Cass 1970).

Barbot, John. 1732.

A description of the coasts of North and South Guinea. In A. Churchill, ed., A Collection of voyages and travels. London. Vol. 5, pp. 1-588.

Beecham, J. 1841.

Ashantee and the Gold Coast. London (reprinted, New York, 1970).

Bianco, B. A., C. R. DeCorse, and J. Howson. 2006.

Beads and other adornment, Chapter 13. In General Services Administration, 2006.

Bilby, K. M. and J. S. Handler. 2004.

Obeah: healing and protection in West Indian slave life. The Journal of Caribbean History 38: 153-183.

Bosman, W. 1721.

A new and accurate description of the coast of Guinea. London (first English translation, published 1705).

Brown, D. A. 2006.

Fairfield Quarter [Fairfield plantation, Virginia]. http://www.daacs.org/resources/sites/FairfieldQuarter/background.html.

Conneau, T. 1976.

A slaver's log book; or 20 years' residence in Africa. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Curtin, P. D. ed. 1967.

Africa Remembered: narratives by West Africans from the era of the slave trade. The University of Wisconsin Press.

DeCorse, C. R. 1989.

Beads as chronological indicators in West African archaeology: a reexamination. Beads: Journal of the Society of Bead Researchers 1: 41-53.

DeCorse, C. R. 1999.

Oceans apart: Africanist perspectives of diaspora archaeology. In T. A. Singleton, ed., "I, Too, Am America": Archaeological Studies of African-American Life. University of Virginia Press. pp. 132-155.

DeCorse, C. R., F. G. Richard, and I. Thiaw. 2003.

Toward a systematic bead description system: a view from the Lower Falemme, Senegal. Journal of African Archaeology 1: 77-109.

Duncan, J. 1847.

Travels in Western Africa in 1845 & 1846. 2 vols. London (reprinted, Frank Cass, London, 1968).

Falconbridge, A. 1788.

An account of the slave trade on the coast of Africa. London. Reprinted Liverpool, 2000 and edited by Christopher Fyfe, pp. 191-230.

General Services Administration, 2006.

New York African Burial Ground Archaeology Final Report (http://www.africanburialground.gov/Report/).

Gordon, A., C. R. Cain, and C. Clatto. 2001.

A report of two seasons of excavation at the Lemp Avenue Site. http://users.stlcc.edu/mfuller/lempdig/Lemp.html.

Great Britain, Board of Trade. 1789.

Part II, Evidence concerning the manner of carrying slaves to the West Indies. Report of the Lords of the Committee of Council . . . concerning the present state of the trade to Africa, and particularly the trade in slaves . . . . London, 1789 (non-paginated).

Handler, J. S. 1997.

An African-Type Healer/Diviner and His Grave Goods: A Burial from a Plantation Slave Cemetery in Barbados, West Indies. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 1: 91-130.

Handler, J. S. 2000.

Slave medicine and obeah in Barbados, circa 1650 to 1834. New West Indian Guide 74: 57-90.

Handler, J. S. 2002.

Survivors of the middle passage: life histories of enslaved Africans in British America. Slavery and Abolition 23: 25-56.

Handler, J. S. and F. W. Lange. 1978.

Plantation slavery in Barbados: An archaeological and historical investigation. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Hawkins, J. 1797.

A history of a voyage to the coast of Africa, and travels into the interior of that country. 2nd ed. Troy, New York.

Heath, B. 1999.

Buttons, beads, and buckles: self-definition within the bounds of slavery. In M. Franklin and G.R. Fesler, eds. Historical Archaeology, Identify Formation and the Interpretation of Ethnicity. Dietz Press, Richmond: Colonial Williamsburg Research Publications, pp. 47-69.

Higman, B. W. 1998.

Montpelier, Jamaica : a plantation community in slavery and freedom, 1739-1912. Mona, Jamaica: University Press of the West Indies.

Hurston, Z. N. 1927.

Cudjo's own story of the last African slaver. The Journal of Negro History 12: 648-663.

Jackson, E. L. 1905.

St. Helena: The historic island. New York.

Jeffery, R. W., ed. 1907.

Dyott's diary, 1781-1845, a selection from the journal of William Dyottt, sometime general in the British Army. 2 vols. London.

Jones, A. 1981.

Théophile Conneau at Galinhas and New Sestos. History in Africa 8: 89-105.

Lambert, S. ed. 1975a.

Minutes of the evidence on the slave trade, 1788 and 1789. House of Commons Sessional Papers of the eighteenth century, vol. 68. Wilmington, Delaware: Scholarly Resources, Inc.

Lambert, S. ed. 1975b.

Minutes of the evidence on the slave trade, 1791 and 1792. House of Commons Sessional Papers of the eighteenth century, vol. 82. Wilmington, Delaware: Scholarly Resources, Inc.

Lambert, S. ed. 1975c.

Report of the Lords of Trade on the slave trade, 1789, Part I. House of Commons Sessional Papers of the eighteenth century, vol. 69. Wilmington, Delaware: Scholarly Resources, Inc.

LaRoche, C. J. 1994.

Beads from the African Burial Ground, New York City: a preliminary assessment. Beads. Journal of the Society of Bead Researchers 6: 2-20.

Law, R. and P. E. Lovejoy, eds. 2001.

The biography of Mahommah Gardo Baquaqua: his passage from slavery to freedom in Africa and America. Princeton: Markus Wiener.

Miller, J. 1988.

Way of Death: merchant capitalism and the Angolan slave trade, 1730-1830. University of Wisconsin Press.

Moore, D. 1997.

Site Report: Historical & Archaeological Investigations of the Shipwreck Henrietta Marie. Key West, Florida: Mel Fisher Maritime Heritage Society.

Mouser, B. L. 1979.

Théophilus Conneau: the saga of a tale. History in Africa 6: 97-107.

Newton, J. 1788.

Thoughts upon the African slave trade. London, 1788. Reprinted in B. Martin, ed., Journal of a slave trader (John Newton) 1750-1754. London, 1962.

Ogundiran, A. 2002.

Of Small Things Remembered: Beads, Cowries, and the Cultural Translations of the Atlantic Experience in Yorubaland. International Journal of African Historical Studies 35(2-3): 427-457.

Posnansky, M. 1999.

West Africanist reflections on African-American archaeology. In T. A. Singleton, ed., "I, Too, Am America": Archaeological Studies of African-American Life. University of Virginia Press. pp. 21-38.

Riland, J., ed. 1827.

Memoirs of a West-Indian planter. Published from an original MS. London.

Robinson, S. 1867.

A sailor boy's experiences aboard a slave ship in the beginning of the present century. Hamilton (reprinted Wigtown, 1996).

Singleton, T. A. 1991.

The archaeology of slave life. In D. C. Campbell, Jr., ed., Before freedom came: African-American Life in the Antebellum South. Richmond: Museum of the Confederacy and Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, pp. 155-175.

Smith, H. F. C., D. M. Last, and Gambo Gubio. 1967.

Ali Eisami Gazormabe of Bornu. In Curtin 1967, 199-216.

Smith, Venture. 1798.

A Narrative of the life and adventures of Venture, a native of Africa: but resident above sixty years in the United States of America. New London, Conn.

Societé de la Moral Chretienne. 1826.

Faits relatifs a la traite des noirs. Comité pour l'abolition de la traite des noirs. Paris.

Stine, L. F., M. A. Cabak, and M. D. Groover. 1996.

Blue beads as African-American cultural symbols. Historical Archaeology 30: 49-75.

Stiverson, G. and P. Butler. 1977.

Virginia in 1732: the travel journal of William Hugh Grove. The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 85: 18-44.

Thorp, D. B. 1988.

Chattel with a soul: The autobiography of a Moravian slave. The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 112: 433-451.

Van Dantzig, A. 1975.

English Bosman and Dutch Bosman: a comparison of texts. History in Africa 2: 185-215 (cf. Vols. 3-7, 9, 11).

Webster, J. 2005.

Looking for the material culture of the Middle Passage. Journal for Maritime Research (Greenwich Eng: National Maritime Museum). December.

Wilkie, L. A. and P. Farnsworth. 2005.

Sampling many pots: an archaeology of memory and tradition at a Bahamian plantation. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Wilkes, I. 1967.

Abu Bakr Al-Siddiq of Timbuktu. In Curtin 1967, pp. 153-169.

Willyams, C. 1796.

An account of the campaign in the West Indies in the year 1794. London.

Winsnes, S. A. trans. and ed. 1992.

Letters on West Africa and the slave trade: Paul Erdmann Isert's Journey to Guinea and the Caribbean islands (1788). The British Academy, Oxford University Press.

Yakubik, J-K and R. Méndez. n.d.

Beyond the Great House: archaeology at Ashland-Belle Helene Plantation. Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism. http://www.crt.state.la.us/archaeology/greathou/tgh.htm.