June 2008 NewsletterISSN: 1933-8651

In this issue we present the following articles, news, announcements, and reviews:

|

Articles, Essays, and Reports

News and Announcements

Conferences and Calls for Papers

Book Reviews

|

African Atlantic Archaeology and Africana Studies:

A Programmatic Agenda

By Akin Ogundiran

In January 2008, Indiana University Press officially published Archaeology of Atlantic Africa and the African Diaspora, a 20-chapter book edited by Toyin Falola and me. The book examines aspects of African experience and the shaping of "African character" both in the spotlight and in the shadow of the Atlantic commercial revolution and its political economy from about 1500 to the 1800s. Privileging the transcripts of material evidence, as well as textual and performative sources, the book underscores the articulation of agencies/subjectivities of African-descended populations with the Atlantic economy and its sociopolitical ramifications from Africa to the Americas, Senegambia to the Swahili Coast, New England to the Southern Cone. The book is conceived as a contribution to both Historical Archaeology and Africana Studies. It benefits from the previous anthologies that have provided discrete though informative regional perspectives on the archaeology of African-descended populations in the US, West Africa, and the Caribbean (DeCorse 2001a; Haviser 1999; Singleton 1999) during the Atlantic Age. My interest here is not to summarize the book or to make a case for its scholarly merits, but to illustrate the broad intellectual agenda that Archaeology of Atlantic Africa and the African Diaspora belongs to. In specific terms, the book is a contribution to African Atlantic Archaeology, a specialty that is devoted to understanding cultural formations by continental Africans and the Africans in the Diaspora during the Atlantic Age. The potential contribution of African Atlantic Archaeology to the intellectual project of Africana Studies is the subject of this essay. [Read or download this full article here in Adobe .pdf format >>>].

[Return to table of contents]

Excavating the South's African American Food History

By Anne Yentsch

This essay is a rewritten and condensed excerpt of chapter three in African American Foodways: Explorations of History & Culture, edited by Anne L. Bower (Univ. of Illinois Press, 2007). Additional chapters of particular interest to archaeologists in that volume include "Food Crops, Medicinal Plants, and the Atlantic Slave Trade," by Robert L. Hall and "Chickens and Chains: Using African American Foodways to Understand Black Identities," by Psyche Williams-Forson. Other chapters in the volume emphasize literary connections, the cultural creation of soul food, black hospitality before World War I, and cookbooks compiled by the National Council of Negroes. Each in its own way displays the divergent talents that contribute to ethnic food studies; provides extensive references to primary and secondary sources; and also offers something of interest to archaeologists working with African American material remains. [Read or download this full article here in Adobe .pdf format >>>].

[Return to table of contents]

Mexico's Cimarron Heritage and Archaeological Record

By Terrance Weik

Little research has been conducted on the archaeology of the African Diaspora in Latin America (Castano 2000; Schavelzon 1999; Singleton 2001; Weik 2004). Mexico is one area that could rapidly help fill this research void, with its numerous plantations and free Afro-Mexican towns. Cimarrones (known as maroons in English), Africans who escaped from slavery, present archaeologists with opportunities to examine social and cultural transformations that resulted from the Transatlantic Slave trade. Investigations of Cimarrones allow us to examine the complexities of human organization, survival strategies, resistance to slavery and racism, and colonial period interactions. Studying Cimarrones also provide an opportunity to understand experiences of (self) emancipated Africans, who receive less attention than enslaved Africans in archaeological research on the African Diaspora. Interesting parallels and connections can be found in antislavery resistance occurring in places as far apart as the Southeastern U.S. and Mexico. A few preliminary archaeological studies have explored the emergence of small towns on the Texas-Mexico border during the 19th century, where Cimarrones and Native Americans clashed and collaborated near settlements such as Bracketteville and Nacimiento. Further south, in the state of Veracruz, brief field research conducted during the summer of 2003 has documented the modern pueblos of Amapa and Yanga, which contain material culture, structures and traditions that relate to 17th to 19th century Cimarron history. This paper describes some of the evidence that was encountered and the potential these places hold for future research. [Read or download this full article here in Adobe .pdf format >>>].

[Return to table of contents]

A Haven from Slavery on Florida's Gulf Coast:

Looking for Evidence of Angola on the Manatee River

By Uzi Baram

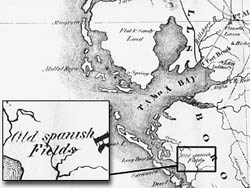

Draining toward the Gulf of Mexico, the Manatee River is one of west central Florida's major rivers. Over its sixty miles, there is material evidence of human habitation from several pre-Columbian sites, a national commemoration of Hernando de Soto's expedition, and county historical markers for the initial Anglo-American settlements. Today, its banks are experiencing urban sprawl from the cities of Palmetto and Bradenton and exurban development. The river is a key to the region's history; but there is a hidden history under the sprawl and the search for the alternative history is the focus of this paper.

In 1990, historian Canter Brown, Jr., published an article in a regional journal that laid out archival insights into a previously unknown maroon community in this southern part of Tampa Bay. A decade later, Vickie Oldham, a documentary filmmaker, began an overview of Sarasota's history with the saga of those escaped slaves. In late 2004, as a community activist she organized a group of scholars for an archaeological search to find material evidence for this history.

The research team includes archaeologists, an ethnographer, a historian, educators, and community activists and we went to the public from the start of the research process (Oldham et al. 2005). The reaction of audiences, the local media, and colleagues ranged from amazement over a hidden history to excitement regarding an important chapter in American history being under the Floridian sprawl.

In this discussion, I will support conclusions from other scholars of maroon archaeology (e.g., Orser 1998, Orser and Funari 2001, Weik 2005, Haviser and MacDonald 2006, Norton and Espenshade 2007). The broad history for escaping slavery in Spanish La Florida will be followed by a discussion of resistance and conclude with the initial steps of the search for the maroon community on the Manatee River on Florida's Gulf Coast. [Read or download this full article here in Adobe .pdf format >>>].

[Return to table of contents]

Aspects of the Atlantic Slave Trade:

Smoking Pipes, Tobacco, and the Middle Passage

By Jerome S. Handler

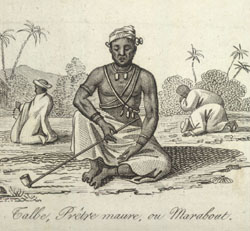

This paper briefly addresses tobacco consumption and pipe smoking in Western Africa, and the relevance of these practices to the Atlantic slave trade as well as to the material culture of captive Africans during their forced passage to the New World.

Although a New World cultigen, tobacco was introduced to Africa by Europeans and by the very early seventeenth century, it seems to have been well established in West and West Central Africa. Its cultivation was observed in Sierra Leone in 1607, and in 1611 a Swiss surgeon remarked on how soldiers in the Kingdom of Kongo relieved their hunger by grinding and igniting tobacco leaves "so that a strong smoke is produced, which they inhale" (Hill 1976: 115; Jones 1983: 61 and note 97).

Not long after its introduction tobacco became a desired commodity among Africans, and from the mid to late seventeenth century it was one of the trade goods Europeans used to acquire slaves. Most of the tobacco Europeans brought to Africa was intended for slave purchase, but some, probably the cheaper grades -- what the French called "tabac de cantine" -- was also distributed to captives on board the slaving vessels.

African consumers chewed tobacco, used it as snuff, and also smoked it in pipes they themselves produced. These were frequently short-stemmed clay bowls of one kind or another, so-called "elbow bend" or "elbow" pipes, into which a detachable hollow wood tube or reed stem, sometimes of considerable length, was inserted. A wide range of "elbow bend" pipes, dating from the early seventeenth-century, have been discovered in a variety of West African archaeological sites from the Middle Niger to the coastal areas of Benin and Ghana. [Read or download this full article here in Adobe .pdf format >>>].

[Return to table of contents]

Pieces of Chocolate:

Surveying Slave and Planter Life

at Chocolate Plantation, Sapelo Island, Georgia

By Nicholas Honerkamp and Rachel L. DeVan

Over four decades ago Reynold J. Ruppe suggested that archaeological survey could reach beyond the discovery level of research (1966). Ruppe proposed that in addition to detecting the presence (or absence) of archaeological remains and defining their spatial and temporal extent, it is possible to develop problem-oriented survey approaches that address a variety of questions. Although Ruppe was specifically concerned with surface surveys in the Southwest United States (1966:314-315), his observations also apply to the subsurface survey data from plantation sites in the Southeast. With the advent of such powerful tools as remote sensing and GIS (Geographic Information Systems), coupled with a landscape archaeology perspective, survey has become much more than reconnaissance.

Such was the case at Chocolate Plantation (9MC96) on Sapelo Island, Georgia. The site is located on the west side of Sapelo, next to the Mud River and expansive spartina marshes, tidal creeks, and estuaries. Most of the Island's habitation sites, both prehistoric and historic, are found on high ground adjacent to navigable waterways (McMichael 1980). Chocolate is distinguished by the presence of substantial tabby foundations associated with an antebellum planter's big house, various outbuildings and support structures, and two rows of slave cabins.

This article presents archeological data generated from the excavation of a modest number of survey units on a systematic grid constructed over the circa 3.7 hectare site. The survey was carried out by a University of Tennessee at Chattanooga (UTC) Archaeological Field School, under the direction of the senior author. Due primarily to the occurrence of the extensive antebellum tabby foundations, previous archaeological approaches have been concentrated, not surprisingly, on those remains (Simmons 2004; Ray Crook, personal communication). While complementing the earlier work, the present study provides baseline survey data for the entire site, rather than a foundation-oriented subset. Although the 2006 survey sample for this site was small (less than 0.1% of the total site area), it was possible to apply GIS techniques to a number of issues that are important to plantation archaeologists and to local Geechee residents, many of whom are descendents of the Sapelo's former slave communities. A detailed final report on this project has been produced (Honerkamp, Crook, and Kroulek 2007), and the present article summarizes some of the data from it. [Read or download this full article here in Adobe .pdf format >>>].

[Return to table of contents]

Not Presentism but Honesty:

Symposium and Lecture Series at Boston University Commemorates

the 200th Anniversary of the Ending of the US-Atlantic Slave Trade

By Mary C. Beaudry

In April and May, 2008, the Department of African American Studies at Boston University held a symposium and a lecture series to acknowledge the ending of the US Atlantic slave trade in 1808. The series was co-sponsored by the university's African Studies Center, American & New England Studies Program, Latin American Studies Program, Women's Studies Program, The Howard Thurman Center, and the Dean of Students.

Prof. Ron Richardson, chair of the Department of African American Studies, noted in opening remarks that America has collective amnesia about the trade, an amnesia that is reflected by the relative lack of commemoration of the end of the US Atlantic slave trade, while in England in 2007 there were seemingly countless events, exhibits, and commemorations of England's exit from the trade. Richardson stated that to accuse the founding fathers on behalf of the many thousands gone is not presentism but honesty; it acknowledges who we are. The aim of the symposium and lecture series was to "open the books" on 1808 and to look at the implications of the closing of the Atlantic trade. [Read or download this full article here in Adobe .pdf format >>>].

[Return to table of contents]

Some Reflections on Relics of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade

in the Historic Town of Badagry, Nigeria

By Alaba Simpson

In recent decades, expanding studies of oral histories and documentary evidence concerning the trans-Atlantic slave trade have undoubtedly improved our understanding of that system and its effects of African cultural diasporas. Interesting oral history information from past indigenous slave dealer communities in West Africa also provides new dimensions to our knowledge regarding past economic and socio-cultural relationships and the existence of diverse mechanisms of the enslavement system that were used to enforce captivity during the period of the trade.

The slave port of Badagry in Nigeria provides us with insights into the history of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, particularly from the view point of contemporary perspectives and appreciation and exhibition of relics from the system of enslavement. The foundational history of Badagry, which is situated in the Lagos State of Nigeria, dates back to approximately 1425 A.D. [Read or download this full article here in Adobe .pdf format >>>].

[Return to table of contents]

Dissertation Abstract:

The Free African American Cultural Landscape: Newport, RI, 1774-1826

By Akeia A.F. Benard

This 2008 dissertation completed at the University of Connecticut examines, through documentary evidence and material culture, the processes of community integration at Newport, development and maintenance of an African American elite, and community disintegration in the form of repatriation of community leaders to Africa. The dissertation also examines the nature and scale of social interaction -- such as community events, marriage patterns, and neighborhood development -- within the African American community between approximately 1774 (the year of the first census of free African Americans in Newport) and 1826 (the year community leaders emigrated to Liberia). This analysis is placed within the context of contemporary theory in African American Ethnohistory and the presentation of African American history in Newport. Census documents, diaries, probates, deeds, and correspondence of the Free African Union Society of Newport offer primary accounts of the lifeways of African Americans in Newport during this time period.

While an African American community developed out of the recognition of a general African identity based on eighteenth century racial ideologies, this dissertation explores the emergence and mechanisms of social stratification within the African American community and the negotiation of racial and class identities. This dissertation serves as a critical and reflexive assessment of African American history in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, specifically critiquing the absence of African American history in Newport public memory, tourism, and the landscape.

[Return to table of contents]

Graduate Programs in African Diaspora Archaeology

By Christopher Fennell

The following compilation provides a list of graduate school programs that can provide concentration and training in African diaspora archaeology subjects. There are currently very few programs that formally offer a graduate degree specializing in this subject area, but there exist many programs that offer graduate degrees in archaeology and include faculty members who specialize in African diaspora subject areas. The list set out below was compiled based on published directories, information provided by the departments, and details sent to me by graduate students and faculty members. This list of programs and of related faculty within each program is not exhaustive. If you are aware of other graduate programs in African diaspora archaeology not listed below, or of additional details concerning those that are listed, please contact me so I can include such information in future compilations.

In addition, graduate programs in African diaspora studies or African-American studies can also be of great benefit to a graduate student seeking to specialize in related archaeological approaches. A list of such programs in African diaspora studies and African-American studies is available on the web site of the Association for Studies of Worldwide African Diasporas, at: www.aswadiaspora.org/links.html.

Ball State University

Department of Anthropology

Degrees offered: MA

Information from the school: The Master of Arts program with a major in anthropology is designed to provide students with a broad understanding of general anthropology as well as experience in a specialized area so they may pursue doctoral studies if desired. Core courses in three major subdisciplines are required, as well as a theory course. Related faculty: Mark Groover. Address: Department of Anthropology, Ball State University, Muncie, Indiana 47306-0435, USA. / Ph: (765) 285-1575 / email: mdgroover@bsu.edu / URL: www.bsu.edu/anthropology/.

College of William and Mary

Department of Anthropology

Degrees offered: MA, PhD

Information from the school: The anthropology of the past, meeting place of ethnography, historical documentation and material culture, informs the program in historical anthropology. The archaeology of colonialism, whether in a Chesapeake, New World or Atlantic context, the archaeology of the lab, whether material culture, zooarchaeology or conservation, as well as theoretical training and field applications, informs the program in archaeology. The MA and MA/PhD programs in historical archaeology and historical anthropology at the College of William and Mary offer faculty expertise and research opportunities for the study of African Diasporic communities in North America, the Caribbean, and South America. The Department's Institute for Historical Biology maintains databases on the bioarchaeology of the Diaspora. Related faculty: Michael Blakey, Joanne Bowen, Marley Brown, Grey Gundaker, Richard Price, Sally Price, Frederick Smith. Address: PO Box 8795 Washington Hall, Room 103 Williamsburg, VA 23187-8795, USA. / Ph: (757) 221 1056/1055 / Fx: (757) 221-1066 / E-mail:crroex@wm.edu / URL: www.wm.edu/anthropology.

George Washington University

Department of Anthropology

Degrees offered: MA

Information from the school: Our master's program in Anthropology is designed to provide students with a comprehensive grounding in the four fields of the discipline: biological anthropology, sociocultural anthropology, archaeology, and linguistics. In addition, students may choose a formal concentration in folklife, international development, or museum training. Related faculty: John Michael Vlach, Stephen C. Lubkemann, and Pamela Cressey (head of Alexandria Public Archaeology). Address: Hortense Amsterdam House, 2110 G Street, NW, Washington, DC 20052 USA / URL: www.gwu.edu/~anth/ (G.W.U.) and oha.alexandriava.gov/archaeology/ (Alexandria Archaeology)

Illinois State University

Department of Sociology and Anthropology

Degrees offered: MA/MS

Information from school's website: The Master's of Historical Archaeology is focused specifically on the study of cultures that either have inhabited the world since the beginning of modern history or which have a long literate tradition. The multidisciplinary approach of the program allows students to take courses from an array of departments including Sociology & Anthropology, History, and Geology-Geography. Instruction focuses on the analysis, examination, and presentation of professional reports on investigation and scholarly studies detailing original research in historical archaeology. Related faculty: Elizabeth Scott. Address: 332 Schroeder Hall, Campus Box 4660, Illinois State University, Normal, IL 61790-4660 USA / URL: www.soa.ilstu.edu/.

Oxford University

School of Archaeology

Degrees offered: MS/MPhil, PhD

Information from school's website: Graduate students are, with the few exceptions noted below, admitted by the Committee for the School of Archaeology. They may opt to study for a Master's degree of one or two year's duration (MSt, MSc, MPhil), or choose to embark on a degree by research (MLitt, DPhil). Prior completion of a Master's degree or equivalent, either at Oxford or elsewhere, is normally required for research students, but it is possible to begin graduate work at Oxford as a Master's student and subsequently decide to proceed onward to the doctoral level. Students and their supervisors are grouped around three main foci, the Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art (archaeological science), the Ashmolean Museum (Classical archaeology) and the Institute of Archaeology (all 'non-science' branches of the subject). The Institute of Archaeology and the Research Laboratory maintain libraries and an extensive range of online resources is also available. Numerous seminar series, for which graduate students are frequent contributors and organisers, explore cutting edge topics on a weekly basis. Related faculty: Dan Hicks. Address: Institute of Archaeology, 36 Beaumont Street, Oxford, OX1 2PG; Phone: +44 (0) 1865 278240 / 613011; e-mail: dan.hicks@arch.ox.ac.uk; URL: www.stx.ox.ac.uk/general/fellows/hicks_dan.

San Diego State University

Department of Anthropology

Degrees offered: MA

Information from the school: When the graduate student enrolls in the Department and achieves conditional or classified graduate standing, he/she is advised by the Graduate Coordinator to develop a program of study designed to provide the breadth, depth, and specialized training necessary for a professional career in Anthropology. Related faculty: Seth Mallios. Address: 5500 Campanile Dr San Diego, CA 92182-6040, USA. / Ph: (619) 594-5527 / Fx: (619) 594-1150 / E-mail:anthro@mail.sdsu.edu / URL: www-rohan.sdsu.edu/~anthro.

Sonoma State University

Department of Anthropology

Degrees offered: MA (in Cultural Resource Management)

Information from school's website: The Master of Arts in Cultural Resources Management (CRM) involves the identification, evaluation and preservation of cultural resources, as mandated by cultural resources legislation and guided by scientific standards within the planning process. The primary objective of the Master's Program in Cultural Resources Management is to produce professionals who are competent in the methods and techniques appropriate for filling cultural resources management and related positions, and who have the theoretical background necessary for research design and data collection and analysis. Related faculty: Adrian Praetzellis, Margaret Purser. Address: 1801 East Cotati Ave., Rohnert Park, CA 94928 USA / URL: www.sonoma.edu/anthropology/.

Syracuse University

Department of Anthropology

Degrees offered: MA, PhD

Information from the school: Graduate study in historical archaeology combines the theory and techniques of anthropological archaeology with the use of documentary source material and oral historical information. The department offers a strong program in historical archaeology, with particular focus on Africa and the African diaspora. However, graduate students receive holistic, four field training in anthropology. In addition, the placement of the Department within the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs and the College of Arts and Sciences affords access to related programs such as museum studies, historic preservation, policy planning, and environmental studies. The program is unique in having several faculty with research foci on Africa and the African diaspora. Related archaeology faculty: Theresa Singleton, Christopher DeCorse, Douglas Armstrong. Related cultural anthropology faculty: John Burdick (Brazil, Latin America), Peter Castro (Africa); Deborah Pellow (Ghana). Address: 209 Maxwell Hall Syracuse, NY 13244-1090, USA / Ph: (315) 443-2200 / Fx: (315) 443-4860 / URL: www.maxwell.syr.edu/anthro/.

University of California, Berkeley

Department of Anthropology

Degrees offered: MA, PhD

Information from the school: Graduate study at Berkeley is characterized by its extraordinary breadth. The department's award-winning faculty, both social cultural and archeaological, engage diverse analytic and substantive problems and work across the United States and around the world. Related faculty: Laurie Wilkie, Paul Farnsworth. Address: 232 Kroeber Hall Berkeley, CA 94720-3710, USA / Ph: (510) 642-3391 / Fx: (510) 643-8557 / URL: anthropology.berkeley.edu.

University of California, Los Angeles

Department of Anthropology

Degrees offered: MA, PhD

Information from the school: Though M.A.-level students specialize in the area of their choice, they are expected to have a basic understanding of all four fields in anthropology (archaeology, biological, sociocultural, and linguistic). A series of "core courses" are offered for those who lack background in one or more fields. In addition to course work, a thesis, based on original research, is expected of all M.A. students to demonstrate their ability to generate and analyze data. Students entering with a master's degree in any field need not repeat this degree, but a basic knowledge of the four fields, as well as competence in a foreign language, is expected and required before beginning doctoral work. At the doctoral level, students specialize more on their particular area(s) of interest than in one of the four subfields. Courses and research are tailored to personal interests and goals in consultation with faculty advisors. The doctoral dissertation is based on original research, typically involving fieldwork. Related faculty: Merrick Posnansky (emeritus). Address: 341 Haines Hall, Box 951553, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1553, USA / Ph: (310) 825-2055 / Fx: (310) 206-7833 / URL: www.anthro.ucla.edu.

University of California, Santa Cruz

Department of Anthropology

Degrees offered: MA, PhD

Information from the school: The doctoral program in anthropological archaeology focuses on the archaeology of late precolonial societies in East and West Africa and North America, and the archaeology of colonial encounters in both regions. The program's focus on the archaeology of colonialism is augmented by departmental strengths in the cultural anthropology of colonial encounters and is further enriched by interdisciplinary relationships with faculty in History, Latino and Latin American Studies, and History of Art and Visual Culture. Doctoral students choose methodological concentrations in any of the following: ceramic materials analysis, landscape and architectural analysis,

zooarchaeology, and chemical and isotopic characterization studies,

singly or in combination. Related faculty: Diane Gifford-Gonzalez, Judith Habicht-Mauche, and J. Cameron Monroe. Other Related faculty/staff: William Hildebrandt, Assaf Yasur-Landau. Address: Department of Anthropology, University of California, Santa Cruz, CA 95060 USA; phone: (831) 459-9920; fax: (831) 459-5900; URL: http://anthro.ucsc.edu.

University of Chicago

Department of Anthropology

Degrees offered: MA, PhD

Information from the school: The Department of Anthropology at the University of Chicago offers a doctoral program with a concentration in archaeology, sociocultural, or linguistic anthropology. Although an M.A. degree is earned during progress towards the Ph.D., no one is admitted to the Department solely to seek the M.A. Related faculty: Shannon Lee Dawdy (U.S., Cuba, Mexico; historical archaeology), Michael Dietler (Kenya, ethnoarchaeology), Stephan Palmie (Cuba), François Richard (West Africa, Senegal), Kesha Fikes (Portugal, Cape Verde), Jean Comaroff and John Comaroff (South Africa). Address: 1126 East 59th Street, Chicago, IL 60637 USA / URL: anthropology.uchicago.edu/.

University of Florida

Department of Anthropology

Degrees offered: MA, PhD

Information from the school: Anthropologists at the University of Florida carry out research in Africa, Latin America and the Carribbean, North America, Asia, and Europe. Our teaching program, at both the graduate and undergraduate levels and in all fields of the discipline, reflects a strong commitment to a cross-cultural, comparative perspective. We have continuing relationships with universities, research centers and institutes, government bureaus, non-governmental institutions, and development agencies in Latin America, the Caribbean, sub-Saharan Africa, and Asia. Related faculty: James Davidson and Peter Schmidt. Address: PO 117305, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA / Ph: (352) 392-2253 / Fx: (352) 392-6929 / URL: www.anthro.ufl.edu.

University of Houston

Department of Anthropology

Degrees offered: MA

Information from the school: The programs of the Department of Anthropology focus on archaeology and ethnology as specialized areas of study. A diverse curriculum provides courses in the major subfields of ethnology, archaeology, linguistics, and physical anthropology as well as in the study of important world regions, such as the United States, North America, Latin America, and Africa. Related faculty: Kenneth Brown. Address: 233 McElhinney, Houston, TX 77204-5020, USA / Ph: (713) 743-3780 / Fx: (713) 743-4287 / E-mail:edmiller@mail.uh.edu / URL: www.uh.edu.

University of Idaho

Department of Sociology, Anthropology, and Justice Studies

Degrees offered: MA

Information from school's website: The University of Idaho's Department of Sociology/Anthropology/Justice Studies offers a Master of Arts degree in Anthropology. This program includes class work, seminars, directed studies, independent research, a thesis, and a combined final oral exam and thesis defense. The curriculum provides sound training in general anthropology, archaeology, physical anthropology, and ethnology. Department research specialities include historical archaeology; prehistoric Northwest archaeology; Plateau Indian ethnography; human evolution; and indigenous peoples of South America. Related faculty: Mark Warner. Address: Phinney Hall Room 101, Moscow, Idaho 83844-1110 USA / URL:

www.class.uidaho.edu/soc_anthro/.

University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign

Department of Anthropology

Degrees offered: MA, PhD

Information from the school: Our program offers M.A. and Ph.D. degrees, including a new M.A. track concentrating on Cultural Heritage and Landscape studies, offered in conjunction with the Department of Landscape Architecture. Our graduate program provides students with in-depth training and education in a range of theoretical and methodological approaches to archaeological investigations. Graduate research and coursework opportunities are also available through the University's African American Studies and Research Program and the Center for African Studies. Related faculty: Christopher Fennell, Helaine Silverman, Marc Perry, Rebecca Ginsburg, Arlene Torres, and Norman Whitten (emeritus). Address: 109 Davenport Hall, 607 S Mathews Ave, Urbana, IL 61801, USA / Ph: (217) 333-3616 / Fx: (217) 244-3490 / E-mail:anthro@uiuc.edu / URL: www.anthro.uiuc.edu.

University of Maryland

Department of Anthropology

Degrees offered: MAA, PhD

Information from the school: The University of Maryland's Master of Applied Anthropology (MAA) is a two-year professional degree designed for those students interested in the practice and application of anthropology. Program emphasis is on the utilization of anthropological knowledge in practical settings. Among the courses offered are studies in archaeology, biology, and culture of the transatlantic African Diaspora. Skills are developed through internships and enhanced by working with professionals in related fields.

The Department of Anthropology offers a Ph.D. The program opened in 2007. Training is offered to historical archaeologists who wish to combine anthropological orientations with the practical application of archaeology in many settings. Opportunities exist with Archaeology in Annapolis, the National Park Service, and in the laboratories within the department. The University of Maryland, College Park has a wide-range of interdisciplinary scholars and opportunities throughout the fields concentrating in the African diaspora.

Related faculty: Mark P. Leone, Paul A. Shackel, Fatimah L.C. Jackson, and Tony L. Whitehead. Address: 1111 Woods Hall, College Park, MD 20742-7415, USA / Ph: (301) 405-1423 / Fx: (301) 314-8305 / E-mail:anthgrad@deans.umd.edu / URL: www.bsos.umd.edu/anth.

University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Department of Anthropology

Degrees offered: MA, PhD

Information from the school: The graduate program in anthropology enables students to become fully competent anthropologists. Robert Paynter and Whitney Battle-Baptiste conduct research at the W.E.B. Du Bois Boyhood Homesite. This work is greatly facilitated by access to and staff support for Du Bois's Papers that are in the Special Collections and Archives of the W.E.B. Du Bois Library at UMass Amherst. Whitney Battle-Baptiste also conducts research on plantations in the U.S. Southeast, the materiality of contemporary African American popular culture, and Black Feminist theory and its implications for archaeology. Enoch Page and Amanda Walker Johnson, colleagues in the Anthropology Department, share research interests in related aspects of the African Diaspora. Faculty and students in the W.E.B. Du Bois Department of Afro American Studies and in the Public History Program of the History Department also share interests in African Diasporic research and presenting it to this country's many publics. Related faculty: Whitney Battle-Baptiste, Robert Paynter, Enoch Page, and Amanda Walker Johnson. Address: 215 Machmer Hall, Amherst, MA 01003 USA / URL: www.umass.edu/anthro/.

University of Massachusetts, Boston

Department of Anthropology

Degrees offered: MA

Information from the school's website: Unlike many other programs in the U.S. that offer M.A. degrees in archaeology, the UMass Boston program is currently devoted solely to historical archaeology and its integration with anthropology and history. The sharpness of focus yet depth of coverage is made possible by the significant number of historical archaeologists and associated colleagues in the program's primary academic departments and affiliated research center, and their joint commitment to a significant set of critical themes in historical archaeology. Related faculty: Stephen Mrozowski. Address: Department of Anthropology, University of Massachusetts-Boston, Boston, MA 02125-3393 USA / Ph: 617-287-6854 / Fx: 617-287-6857/ URL: www.umb.edu/academics/departments/anthropology/.

University of Montana

Department of Anthropology

Degrees offered: MA, PhD

Information from the school: The Cultural Heritage Option is a way to earn the MA degree in anthropology while focusing on methods and theories related to preserving the culture, heritage, and diversity of all peoples. It is designed to produce professionals in the many areas of culture heritage preservation who are firmly grounded in the fundamentals of anthropology. Related faculty: Kelly J. Dixon and Gregory Campbell. Address: Social Science Bldg 235, 32 Campus Drive Missoula, MT 59812, USA / Ph: (406) 243-2693 / Fx: (406) 243-4918 / E-mail:linda.mclean@umontana.edu / URL: www.umt.edu/anthro.

University of Pennsylvania

Department of Anthropology

Degrees offered: MA, PhD

Information from the school: Our department is unique in that it offers a four-field approach, providing breadth of training. The core courses for the Masters (MSc) and PhD programs provide an in-depth introduction to Anthropology as a whole. Because of the broad education offered, graduates and advanced students of the program would be qualified to teach in areas beyond their own specialty, resulting in multiple teaching opportunities. Historical Archaeology has been taught at Penn since 1960/1961 and there has been a graduate concentration in the discipline for over forty years. A number of Penn graduate students have worked on aspects of African Diaspora Archaeology carrying out projects in Africa (South Africa) itself and in both Latin American (West Indies) and in North America. Currently a number of students are very interested in the subject of plantations and in expanding the scope of such studies beyond North America. Related faculty: Robert Schuyler. Address: University Museum Rm. 323, 3260 South Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104-6398 USA / URL: www.sas.upenn.edu/anthro/.

University of South Carolina

Department of Anthropology

Degrees offered: MA, PhD

Information from the school: The Department offers the M.A. and, as of 2005, the Ph.D. in Anthropology. Our program offers instruction in the four traditional sub-fields of anthropology: archaeology, cultural anthropology, linguistic anthropology, and physical/biological anthropology. In this we are unusual. As of 1993, the American Anthropological Association had noted that only 28% of all departments had faculty in all of the four traditional sub-fields. While students are asked to specialize in one of these fields, we particularly seek students who wish to cross the boundaries between fields and combine them in their graduate work. Particular areas are African American historical archaeology (Kelly, Weik, and Clement), African prehistoric archaeology and ethnoarchaeology (Casey), African historical archaeology (Kelly), ethnobotany (Wagner) and Eastern North America (Wagner and Cobb), and bioarchaeology in Mexico (Cahue). The South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology also has several archaeologists working on prehistoric and historic archaeology of the Southeast and a very large collection of materials from the state. Related faculty: Kenneth Kelly, Terrance Weik, Joanna Casey, Gail Wagner, Charles Cobb (Director, SCIAA), Adam King (SCIAA), Christopher Clement (SCIAA) and Leland Ferguson (emeritus). Address: 1512 Pendleton Street, Hamilton College Room 317, Columbia, SC 29208, USA / Ph: (803) 777-6500 / Fx: (803) 777-0259 / E-mail: anthroinfo@gwm.sc.edu / URL: www.cas.sc.edu/ANTH/.

University of Southern Mississippi

Department of Anthropology and Sociology

Degrees offered: MA

Information from the school: The graduate program emphasizes exposure to the four fields of anthropology as a means of preparing for further graduate study, applying anthropological principles in the public service or government sectors, or teaching at the undergraduate level. At the same time we expect students to develop an in-depth grounding in their subfield of interest, from theoretical, methodological, and practice standpoints. We also encourage development of a personal research interest as quickly as possible, ultimately expressed as thesis research. We encourage students to explore topics about which the faculty can provide useful input either through coursework, directed reading, or personal expertise. Related faculty: Amy L. Young.

Address: 118 College Dr #5074, Hattiesburg, MS 39406-0001, USA / Ph: (601) 266-4306 / Fx: (601) 266-6373 / E-mail:antsoc@usm.edu / URL: www.usm.edu/antsoc.

University of Texas, Austin

Department of Anthropology

Degrees offered: MA, PhD

Information from the school: Archaeology at the University of Texas

reflects the breadth of specialization of its faculty, and its strong links with other disciplines. The program enjoys strong ties with Geography, Classics, Latin American Studies, Asian Studies, Social, Cultural, Folklore and Public Culture, Linguistics, and Physical Anthropology. A strong and active group of graduate students, the presence of the Texas Archeological Research Lab, major CRM firms, and offices in State Government make Austin's community of archaeologists and related scholars exceptionally large and diverse. Graduate programs and tracks within Anthropology include the African diaspora graduate program, Borderlands, and Activist Anthropology. Related faculty in Archaeology and African Diaspora studies: Maria Franklin (historical archaeology, North America), Samuel Wilson (prehistory and ethnohistory, Caribbean), James Denbow (prehistory, Africa), Edmund Gordon (social anthropology, Latin America), Jafari Allen (social anthropology and folklore/public culture, Caribbean and North America), Joao Vargas (social anthropology, Brazil and North America), Jemima Pierre (social anthropology, West Africa and North America). Address: Department of Anthropology, 1 University Station C3200, Austin, TX 78712-0303, USA / Ph: (512) 471-4206 / Fx: (512) 471-6535 / for information on the anthropology graduate program and admissions contact Andi Shively at ashively@mail.utexas.edu / URL:

www.utexas.edu/cola/depts/anthropology/.

University of Virginia

Department of Anthropology

Degrees offered: MA, PhD

Information from the school: The archaeology section of the department includes eight faculty whose research and teaching examine anthropological questions through the study of past societies. The interests of the faculty and graduate students span the Old and New Worlds -- specifically North America, South America, Africa, and the Near East -- and the prehistoric through historic periods. In each of these areas we emphasize the integration of anthropological theory with archaeological field methods, artifact analysis, and analytical approaches. Related faculty: Jeffrey Hantman, Adria LaViolette, Fraser Neiman, and Elizabeth Arkush. Address: PO Box 400120, Charlottesville, VA 22904-4120, USA / Ph: (434) 924-7044 / Fx: (434) 924-1350 / URL: www.virginia.edu/~anthro/.

[Return to table of contents]

Society for Georgia Archaeology Publishes

Two-Part Volume on African-American Archaeology

By J. W. Joseph

The Society for Georgia Archaeology (SGA) has published "Material Reflections of Georgia's African-American Past" as a two-part edition of Early Georgia, issues 35(2) and 36(1). Guest edited by J. W. Joseph and containing 11 articles, these publications look at African-American landscapes, architecture, material culture, and lifeways as revealed by archaeological research in Georgia.

Articles in these volumes include: African-American Life in Georgia Through the Archaeological Looking Glass, by J. W. Joseph; Data Recovery Excavations at the St. Annes Slave Settlement, St. Simons Island, Georgia, by Scott Butler; African-American Contributions to Savannah's Historic Landscapes, by Bradford Botwick; Landownership and Hardship: Interpreting the Landscape of an African-American Community in Eastern Gwinnett County, 1870-1950, by Jeffrey L. Holland; Archaeology of a Tenant Farming Landscape: The Free Cabin Site, Hephzibah, Georgia, by Natalie Adams and Mark Swanson; Residential and Communal Landscapes at the Ford Plantation Development, Richmond Hill, Georgia, by Thomas G. Whitley; South of Hell's Gate: Life at the North End Plantation, Ossabaw Island, Georgia, by Daniel T. Elliott; Necessity or Commodity?: An Analysis of the Ford Plantation Colonoware, Bryan County, Georgia, by Nicole Isenbarger; Home-crafted "Brick" Grave Markers in the African-American Section of Memory Hill Cemetery, Milledgeville, Georgia, by James J. D'Angelo; "A City Slave is Almost a Freeman" . . . Or Not?, by Rita F. Elliott; and Springfield: An Archaeological History of a Free African-American Community from the Revolution to the Civil War, by J. W. Joseph.

Compilations of these articles in pdf format on CD are available for purchase. To order, submit a check for $11 made payable for the Society for Georgia Archaeology as well as a letter with your name and address to J. W. Joseph, New South Associates, 6150 East Ponce de Leon Avenue, Stone Mountain, GA 30083. Early Georgia is a copyrighted publication and unauthorized distribution of articles is prohibited by law. For further information about the SGA as well as membership applications, visit www.thesga.org.

[Return to table of contents]

States Lead Slavery Apology Movement

By Christine Vestal

Stateline.org Staff Writer

April 5, 2008

Article posted online by the Stateline.org at:

http://www.stateline.org/live/details/story?contentId=298236.

Copyright 2008 Stateline.org.

As Americans mark the 40th anniversary of the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., more states are apologizing for their historic role in slavery in an effort to begin healing the wounds created by what many have called the country's "original sin."

Florida last month became the sixth state to adopt a resolution expressing "profound regret for the shameful chapter" in the state's history and promoting "healing and reconciliation among all Floridians."

Alabama, Maryland, North Carolina, New Jersey and Virginia had previously done so, and two other states -- Nebraska and Missouri -- are considering similar resolutions this year.

National black leaders applaud these gestures as an important step in reconciling the nation's long-standing racial differences, but caution that further actions, including reparations, are needed.

"I think it's very productive for states to look at their roles in the slavery movement. It's a good place to start," said Hilary Shelton of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. But he said, "unless further discussions follow, their actions will be viewed as very hollow."

All six state resolutions passed with near unanimous approval, although debates that preceded passage focused on whether an official apology amounts to an admission of guilt that could lead to calls for reparations -- payments to the descendants of slaves for their suffering and lost economic opportunities.

The same issue has stymied efforts at the federal level to issue a national apology.

Last year, Tennessee Democrat Rep. Steve Cohen proposed that the federal government apologize for slavery and the so-called Jim Crow laws that victimized blacks after the Civil War. So far, Cohen's bill has not moved and requests for a presidential apology remain unanswered.

But at least one governor, Florida Republican Charlie Crist, has not shied away from the issue of reparations. When he signed Florida's apology resolution last month, Crist said he was open to considering financial reparations -- not this year, but when the state's financial situation improves.

"I was floored. He had absolutely no hesitation," said author Ronald Walters, a leader in the push for reparations. "No other governor has ever done that."

In fact, several states have tried to put a lid on the issue by making clear their apologies are not a step toward reparations.

In Georgia, the state with the second largest pre-Civil War slave population, Gov. Sonny Perdue and other Republican politicians rejected a 2007 apology proposal, because they said it could make the state liable for financial reparations.

The states' apology movement comes as a reaction to a highly-publicized, national push for reparations that peaked in 2002, Walters said. Since then, black state lawmakers decided reparations may not be possible any time soon, but an apology or expression of regret could start the process, he said.

In 2001, a group of black lawyers sued several U.S. insurance companies for having written policies on slaves for their owners. That same year, black leaders unsuccessfully urged President Bush to join a United Nation's sponsored conference on racism and reparations.

Several insurance companies later apologized for their role in enabling slavery, and California enacted a law calling on every insurance company in the state to research and report to the state its historical connections to the slave trade.

But the movement faded over the next four years, leading black lawmakers in several states to take a different approach, said Walters, who as a scholar at the University of Maryland, was instrumental in developing the state's 2006 legislative apology proposal.

Maryland in 2006 was the first state to consider an apology resolution, but Virginia -- the state that once had the largest slave population in the country (490,865, according to an 1860 census) -- in February 2007 became the first to enact a resolution.

"Virginia was the leader," said Democratic state Sen. Henry Marsh, III. "We started a dialog concerning slavery and race relations which we had hoped would happen. Other states immediately began calling us, asking how we did it," said Marsh, who sponsored the resolution.

Maryland Gov. Martin O'Malley (D) signed a resolution in March 2007 and governors in Alabama, New Jersey and North Carolina signed similar bills later in the year.

This year, Missouri supporters of an apology, which failed to pass the legislature last year, say the action would help heal racial wounds in a state that was so divided during the Civil War that it sent troops to both sides.

The Show Me state also is known for its 1856 court ruling denying a slave named Dred Scott citizenship rights. The decision, later upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court, led to enactment of the 13th and14th amendments to the Constitution, which abolished slavery and established legal rights for former slaves. As further evidence of Missouri's historical conflict over slavery, it later became the only state to enact its own emancipation law.

The recent apologies are not the first time states have taken action against slavery ahead of the federal government. In 1777, more than eight decades before President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation freeing slaves in the South, Vermont passed a law declaring the slave trade illegal. New York enacted a similar statute the following year.

"This is the moment for a national apology, because we have a historical first with a black candidate running in the Democratic party," said Carol Swain of Vanderbilt University, who has urged President Bush to hold a Rose Garden ceremony to apologize for slavery.

"I expect states will continue to apologize, state-by-state, in a piecemeal, federalist fashion, and it might make it easier for the federal government to act," Swain said.

[Return to table of contents]

New Book

Africa, Brazil and the Construction of Trans Atlantic Black Identities

Edited by Livio Sansone, Elisee Soumonni, and Boubacar Barry.

Africa World Press, Trenton, New Jersey; Paperback, 356 pp., ISBN-13: 978-1592215270, January 2008.

Description from the Publisher:

The flow of ideas about race, anti-racism and black or African identity across the Atlantic is the focus of this volume of essays drawn from a very special international South-South workshop held on the island of Goree, Senegal, in December 2002, the aim of which was twofold.

First, it critically assessed the study of fluxes and refluxes, ruptures and reciprocal influences in the relations between the two shores of the Atlantic. Certainly, the relative lack of direct contact between Africa and the New World over the last century helps to explain why in Africa, as well as in Latin America, the debate over notions of race and ethnic identity has received more attention than the historical phenomena of civilization, metissage and the relationship of domination between the North and South. The workshop also scrutinized the agenda of the leading researchers of this field of study (classic scholars, e.g. Melville Herskovits, C. Anta Diopp, Roger Bastide and Pierre Verger, as well as more contemporary scholars).

Second, the workshop aimed at creating a common field from which a number of topics for joint research projects on the double dimension Africa/Diaspora can emerge: how to reestablish direct South-South contacts across the Atlantic and bring to the Black Atlantic a Southern perspective, by broadening the scope of this notion and making it more cosmopolitan and genuinely transnational by trespassing the magic limits of the English-speaking world and confronting the colonial legacy of Spain, Portugal, France and the Netherlands in the New World. Such an attempt cries for new comparative studies, the methodology of which should be closely scrutinized under the light of our epoch characterized by a growing set of global ethnic icons, which make the distinction between local specificities and grand transnational ethnic or liberation projects increasingly difficult to pinpoint.

The thirteen contributors to the book write from different positions and perspectives, but focus on ideas in transit and the transit of ideas. The organizers hold firmly that, especially in the making and deconstructing of notions of race and of different races, little is as local as often celebrated. If this is always the case in the processes of racialization that have accompanied the making of the modern world more generally, it is even more pronounced in the context of black versus white relations, a context that comes into being through a gigantic international operation the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

[Return to table of contents]

New Book

Themes in West Africa's History

Edited by Emmanuel Kwaku Akyeampong.

Ohio University Press; Paperback, 288 pp., ISBN-13: 978-0-8214-1641-9, 2008.

Description from the Publisher:

There has long been a need for a new textbook on West Africa's history. In Themes in West Africa's History, editor Emmanuel Kwaku Akyeampong and his contributors meet this need, examining key themes in West Africa's prehistory to the present through the lenses of their different disciplines.

The contents of the book comprise an introduction and thirteen chapters divided into three parts. Each chapter provides an overview of existing literature on major topics, as well as a short list of recommended reading, and breaks new ground through the incorporation of original research. The first part of the book examines paths to a West African past, including perspectives from archaeology, ecology and culture, linguistics, and oral traditions. Part two probes environment, society, and agency and historical change through essays on the slave trade, social inequality, religious interaction, poverty, disease, and urbanization. Part three sheds light on contemporary West Africa in exploring how economic and political developments have shaped religious expression and identity in significant ways.

Themes in West Africa's History represents a range of intellectual views and interpretations from leading scholars on West Africa's history. It will appeal to college undergraduates, graduate students, and scholars in the way it draws on different disciplines and expertise to bring together key themes in West Africa's history, from prehistory to the present.

[Return to table of contents]

Call for Papers

Black Diaspora and Germany Across the Centuries

Conference at the German Historical Institute

Washington, D.C., March 19-21, 2009

Persons of African descent have been present in Europe throughout the past millennium. During the eleventh and twelfth centuries, Africans crossed the Mediterranean to Spain, Sicily, and Italy or made their way to Europe via the Middle East and the Byzantine Empire. In later centuries, the system of transatlantic trade brought black people from the different regions of the Americas to Europe.

In Central Europe, African "court moors" became increasingly present during the Early Modern Period and were an integral part of courtly representation. As a result of exchange processes between Europe, Africa, and the West Indies, the social roles of blacks in Europe and European discourses on blacks diversified over time. By the beginning of the eighteenth century, an increasing number of black Europeans lived in middle-class households, especially those of retired colonial officials, plantation owners or merchants residing in Europe. Others lived independently as seamen or as guild members. Transatlantic chattel slavery, however, fundamentally reconfigured Afro-European relations and transformed perceptions of black people throughout the Atlantic World. Over time, black people were increasingly referred to as "slaves" or "negroes" instead of "moors," an older term associated with, among other things, images of brave warriors that derived from the presence of black soldiers in the armies of the Islamic Empire on the Iberian Peninsula and humanist images of a Christian "land of the moors" ruled by a mythical Prester John in Ethiopia.

By the early nineteenth century, racist views on blacks had found broad public acceptance in Europe. Scientific racism, a branch of ethnology that began to infiltrate Western science from the 1840s onward, further consolidated notions of black inferiority and was widely used to justify the continued enslavement of African peoples. Simultaneously, proslavery arguments were vehemently challenged by Enlightenment ideas of human equality, which gained broader significance on both sides of the Atlantic through the rise of various abolitionist and revolutionary movements. This dialectical contest between racial egalitarianism and white supremacy persisted well into the early twentieth century, when the latter reemerged forcefully in the guise of European imperialism.

The conference "Black Diaspora and Germany Across the Centuries" will retrace these processes of change and revaluation from the eleventh century to the beginning of World War I. Particular emphasis will be laid on the interactions between blacks of various origins (the Americas, the Caribbean, Byzantine Empire, Africa, or born in Europe) and people in the German-speaking parts of Europe. Researchers of all disciplines are invited to discuss continuities and ruptures in this history of mutual perception and contact: migration, art and court historians, American, German and African studies as well as scholars from the field of cultural studies, literature, sociology, musicology, linguistics, etc.

Possible conference topics include: (1) Geopolitical and social spaces of communication and interaction: Which geographical areas and groups of individuals or social classes were involved in processes of exchange? What kind of action repertoires did these spaces leave or offer to people of color? (2) Perception and appropriation of African culture, art, music, etc. and their representations in various contexts (e.g. European court cultures, literature, art production). (3) Altering influence of religious, philosophical, and scientific discourses on modes of Afro-European contacts. (4) Race/Racism vs. egalitarianism as discourse and social practice in the African-German encounter.

Please send a proposal of no more than 500 words and a brief CV to Martin Klimke at klimke@ghi-dc.org; website http://www.ghi-dc.org. The deadline for submission is October 15, 2008. Participants will be notified by mid-November. The conference, held in English, will focus on discussing 5,000 to 6,000 word, precirculated papers (due February 1, 2009). Expenses for travel and accommodation will be covered. Conveners: Martin Klimke (GHI Washington), Anne Kuhlmann-Smirnov (History Department, University of Bremen), Mischa Honeck (Heidelberg Center for American Studies, University of Heidelberg).

[Return to table of contents]

Call for Papers

Society for Historical Archaeology

2009 Conference on Historical and Underwater Archaeology

Ties that Divide: Trade, Conflict and Borders.

Fairmont Royal York Hotel

Toronto, Canada, January 6-11, 2009.

The 2009 conference theme speaks to Toronto’s place in the Great Lakes and its role as an early centre of interaction, exchange and trade between Aboriginal and European nations at the beginnings of the "New World Experience" for this part of the continent. It further speaks to the persistent frontier defined by the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River, and to the conflict between Aboriginal, French, British, American, and Canadian peoples over territory now divided by the Canada-United States border. The conference theme also invites topics beyond a regional focus, since Conflict and Trade, in the broadest application of the concepts, are universal dimensions of past and present life. Likewise Borders, to constrain, separate, and transcend, is a concept that plays out across the entire human experience, such as between urban and rural life, between genders, age and ethnicities enhancing identity, between the disciplines of archaeology, anthropology and history, between underwater and land based archaeology, and between the archaeologist and others who also claim an interest in and ownership of the past. We hope that you will visit us in Toronto, a city that both celebrates and transcends its past and global present with vibrant and diverse museums, galleries, neighborhoods and cuisines that showcase all of the world's cultures that now call Toronto home. Call for papers opens May 1, 2008; late submission deadline, July 1, 2008.

The 2009 conference theme speaks to Toronto’s place in the Great Lakes and its role as an early centre of interaction, exchange and trade between Aboriginal and European nations at the beginnings of the "New World Experience" for this part of the continent. It further speaks to the persistent frontier defined by the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River, and to the conflict between Aboriginal, French, British, American, and Canadian peoples over territory now divided by the Canada-United States border. The conference theme also invites topics beyond a regional focus, since Conflict and Trade, in the broadest application of the concepts, are universal dimensions of past and present life. Likewise Borders, to constrain, separate, and transcend, is a concept that plays out across the entire human experience, such as between urban and rural life, between genders, age and ethnicities enhancing identity, between the disciplines of archaeology, anthropology and history, between underwater and land based archaeology, and between the archaeologist and others who also claim an interest in and ownership of the past. We hope that you will visit us in Toronto, a city that both celebrates and transcends its past and global present with vibrant and diverse museums, galleries, neighborhoods and cuisines that showcase all of the world's cultures that now call Toronto home. Call for papers opens May 1, 2008; late submission deadline, July 1, 2008.

The African Diaspora Archaeology Network will host its annual forum meeting at this SHA conference, with a theme of "African Heritage in Canada." Discussants include Karolyn Smardz Frost, Catherine Cottreau-Robins, Paul Lovejoy, and Heather MacLeod-Leslie, with Chris Fennell as organizer and moderator. Abstract: African diaspora sites in Canada include a spectrum of earliest occupations, through Black Loyalist communities established in the late 1700s following the American Revolutionary War, emancipation havens of the early 1800s, and African Canadian settlements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In addition to research projects focusing on the historical dynamics of such communities within Canada, many sites of African American heritage in the United States had significant connections with the movement of individuals and families to such havens in Canada in the early 19th century. This forum will provide a discussion of current trends and primary issues in research projects concerning African heritage in Canada. Related research questions include: social and economic dynamics impacting such communities; networks traversing the American and Canadian border; responses to slavery and racialization; agencies of resistance and abolition; continuing developments of particular African cultural beliefs and practices; and changing contours of social group networks.

[Return to table of contents]

Book Review

Marcus Rediker. The Slave Ship: A Human History. New York: Viking/Penguin, 2007, 448 pp.

$27.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-0670-01823-9.

Reviewed for the African Diaspora Archaeology Newsletter by Fred L. McGhee, Ph.D., Fred L. McGhee & Associates.

Ten years after my exhortation to move the field "towards a postcolonial nautical archaeology" (McGhee 1998), it has been interesting to watch developments within nautical archaeology unfold. The response of the professional underwater archaeological community appears to have been the undertaking of research initiatives to locate and excavate more slave shipwrecks. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration funding has been used in several of these efforts, examples of which include the search for the wreck of the Trouvadore by the Turks & Caicos Museum (Sadler 2008), and the search for the remains of the Guerrero off the coast of Key Largo, Florida (Swanson 2004). "A total of 825 documented losses at sea are recorded among the 27,000 entries in the Transatlantic Slave Trade Database (Eltis et al. 1999), with 183 of these losses occurring either whilst slaving or after embarkation (that is, with African captives almost certainly aboard)" (Webster 2008), so this remains a wide open field.

It has been gratifying to see the underwater archaeology community take the "data poor" (Singleton and Bograd 1995) portion of my critique for action. There certainly has always been a need for more fieldwork in this area. Unfortunately the other aspects of what I said, and their implications, remain unresolved. It is here where Marcus Rediker has done the underwater archaeology community, especially nautical archaeologists, a favor. His "human history" of this ghoulish commerce should help put to rest the notion that slave shipwreck archaeology is "nautical" archaeology in any sense that matters, and that the middle-range theory premises that have characterized nautical archaeology since its inception in the 1970s are ill-suited to the study of slave shipwrecks:

Unfortunately, many archaeologists have seen Binford's methods of studying site-formation process as an end in themselves. In many cases, the development of middle range theory has become the research goal rather than the means to connect archaeological data with high-level, abstract explanations . . . although such studies increase our interpretive abilities, they contribute little to the advancement of our understanding of human behavior (Maschner 1996:469).

This is not to say that nautical archaeology has nothing to offer. But while a focus on the shipbuilding technology involved in the construction or reconstruction of slave ships would certainly be insightful -- and rather Eurocentric -- is that really the point?

In his note "to the reader" at the beginning of Black Reconstruction, W.E.B. Du Bois (1935) dryly observed in 1934 that "the story of transplanting millions of Africans to the new world, and of their bondage for four centuries for four centuries, is a fascinating one" filled with human drama of massive proportions. The great strength of Rediker's book lies in its insistence that there are people in this story, not statistics, obfuscatory categories, artifact typologies, or shipwreck parts, and that the proper vantage point for studying this subject is the lived all-too-human experiences of the people engaged in the drama:

An ethnography of the slave ship helps to demonstrate not only the cruel truth of what one group of people (or several) was willing to do to others for money -- or, better, capital -- but also how they managed in crucial respects to hide the reality and consequences of their actions from themselves and from posterity (Rediker 2007: 12).

Another strength of Rediker's book is its recognition and exploration of the role of the slave trade in the making of global capitalism. While his book is filled with many anecdotes of racist savagery and unspeakable horror, the book maintains a satisfying focus on the big picture while illuminating the details of these "machines of death" and their effects on the sponsors, captains, crew and cargo of these voyages.

The book is organized into ten chapters plus an introduction and an epilogue. Each chapter builds upon earlier chapters, with the beginning chapters (chapters 1-3) furnishing overall background, the middle four chapters providing description and interpretation of the experiences of the enslaved, crew and captain, and the last three chapters delivering skillful and deeply humanistic summary and interpretation.

Rediker's concern for the individual lived experiences of the participants in the trade is aided immensely by his command of the history of what life at sea is like. While scholars have been using the narrative of Olaudah Equiano to illuminate the experiences of enslavement for decades (Burnside and Robotham 1997), chapter 8 of The Slave Ship titled "The Sailor's Vast Machine" contains a learned and astute description of work and suffering at sea. What sticks out is violence, and the shocking degree to which physical and emotional terror was used as a tool for control and psychosexual masochism. Rediker rightly points out that both captives and crew were being exploited by the captain, officers, and sponsors of slave ship voyages, without going so far as to suggest that the sailors somehow had it worse than the slaves. Far from it; Rediker makes clear the degree to which the nascent concept of "race" was lived out onboard, and relates truly debauched tales of rape, torture, concubinage, and murder of essentially helpless children.

Anthropologically inclined readers will find much of interest in chapter 9 of Rediker's book, titled "From Captives to Shipmates." The argument is of course not new; Mintz and Price raised it in the 1970s as have others. In this chapter Rediker discusses favored anthropology themes such as resistance, revolt, music, dance, and other dimensions of the ethnogenisis of African-American culture. On page 305 he observes:

Slowly, in ways surviving documents do not allow us to see in detail, the idiom of kinship broadened, from immediate family to messes, to workmates, to friends, to countrymen and -- women, to the whole of the lower deck.

And in so observing, Rediker has given underwater archaeologists of the slave trade and the slave ship a research agenda. It's an agenda with which I happen to agree and that I have discussed in greater detail elsewhere (McGhee 2007).

Rediker ends his book with a discussion of the fight to end the slave trade and with the moving testimony of cast-off and dying sailors being cared for by enslaved people in Caribbean ports. He writes, "Theirs was the most generous and inclusive conception of humanity I discovered in the course of my research for this book."

I wonder what conceptions of humanity continue to motivate certain anti-treasure hunting nautical archaeologists. The Henrietta Marie and Fredensborg remain the two most representative archaeological examples of slave ships in existence. The former, first located in the water by Moe Molinar a Panamanian of African descent in the employ of treasure hunter Mel Fisher, is particularly important. Yet it took an African-American recreational SCUBA diving club, the National Association of Black SCUBA Divers, to denote and demonstrate that shipwreck's importance and to bring its significance to wide attention. Properly trained nautical archaeologists still won't publicly touch that wreck with a ten-foot pole. Although they apparently gladly touch the significance of the H.L. Hunley a noted Civil War Confederate submarine.

The moral message of my 1998 article unfortunately remains.

References Cited

Burnside, Madeleine and Rosemarie Robotham

1997 Spirits of the Passage. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Cottman, Michael H.

1999 The Wreck of the Henrietta Marie. New York: Harmony Books.

Eltis David, Behrendt S.D., Richardson D., Klein H.S.

1999 The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade CD-ROM (TSTD). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Eltis, David, Richardson, D., Florentino, M.

2007 Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade: a Revised and Enlarged Database, 1500-1867. Available online at: http://ahds.ac.uk/catalogue/collection.htm?uri=hist-5584-1.

McGhee, Fred L.

1998 Towards a Postcolonial Nautical Archaeology. Assemblage 3:3. Available online at http://www.assemblage.group.shef.ac.uk/3/3mcghee.htm.

2007 Maritime Archaeology and the African Diaspora. In Archaeology of Atlantic Africa and the African Diaspora, edited by Akinwumi Ogundiran and Toyin Falola, pp. 384-394.

Maschner, H. D.G.

1996 Middle Range Theory. In The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, edited by B. M. Fagan, pp. 469. Oxford University Press, New York.

Mintz, Sidney, and Richard Price

1992 The Birth of African-American Culture. Boston: Beacon Press.

Sadler, Nigel

2008 The Trouvadore Project: The Search for a Slave Ship and its Cultural Importance. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 12 (1) 53-80. Available online; Digital Object Identifier: 10.1007/s10761-008-0056-8.

Singleton, T. A. and M. D. Bograd

1995 The Archaeology of the African Diaspora in the Americas. Guides to the Archaeological Literature of the Immigrant Experience in America, No. 2. Society for Historical Archaeology, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Svalesen, Leif

2000 The Slave Ship Fredensborg. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Swanson Gail

2005 The Slave Ship Guerrero. West Conshohocken, PA:

Infinity Press.

Webster, Jane

2008 Slave Ships and Maritime Archaeology: An Overview. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 12(1), 6-19. Available online; Digital Object Identifier: 10.1007/s10761-007-0038-2.

[Return to table of contents]

Book Review

Laurie A. Wilkie and Paul Farnsworth. Sampling Many Pots: An Archaeology of Memory and Tradition at a Bahamian Plantation. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2005, 354 pp., cloth, $65.00, ISBN-13: 9780813028248.

Reviewed for the African Diaspora Archaeology Newsletter by Chris Espenshade, New South Associates, Inc.

This book should be on the must-read list of all subscribers to the newsletter. Although I have my minor quibbles with the volume, I found it challenging, interesting, and thoroughly worthwhile. I offer somewhat lengthy discussions of what I perceive as possible weaknesses of the study, yet I applaud the overall effort.

I believe that most readers will find this book a compelling study in African-Caribbean culture change and identity. The work benefits from good contexts, extensive excavations and analyses, and a moderately good archival record. The volume looks at the creation and maintenance of individual and corporate identities by a diverse group of African Caribbeans including African-born apprentices, enslaved creoles from the Bahamas, and enslaved African Americans brought to the Bahamas from South Carolina. The study is especially interesting because the planter was an outspoken ameliorist and provided written instructions on the care of his enslaved and apprenticed personnel. The authors, Laurie Wilkie and Paul Farnsworth, demonstrate a broad knowledge of West African ethnohistory and ethnography, and also are clearly current on the trends and recent findings of archaeology of the Diaspora. I applaud their focus on individuals as key actors in any tradition. There is much good archaeology and anthropology in this volume.

On the other hand, I believe certain readers may find the study to be mildly frustrating. Some may see the authors as pushing the envelope at numerous junctures. Whenever there are multiple possible explanations for an artifact or a behavior, the authors advocate African memory and African-derived traditions as the preferred explanations.

The first chapter is challenging. The subjects of memory and identity have not been widely addressed in archaeology, and the authors must borrow, or at least touch on, harmony ideology, sociocultural anthropology, modern psychology, practice, agency, structuration, performance, habitus, doxa, long-term and short-term memory, and tradition. When all is said and done, the authors end up with a stance that seems inherently sensible and attractive (p. 8):

We believe that individuals engage in meaningful, discursive social relations on a daily basis. Through their everyday practice, individuals reaffirm allegiances, and differences, with others and actively define their position within their broader community. Actors, depending on the specific context of social interaction and their own sense of self and experience, may or may not be conscious of how their actions convey meanings to others.

Chapter 2 presents an overview of Bahamian history from native Indian occupations up to the Loyalist period, when Clifton Plantation was established. Chapter 3 addresses the various sources of members of African Caribbean culture in the late eighteenth century.

The fourth chapter identifies the people of Clifton plantation, including the planter and his family, the apprentices (in theory, free men of African birth), and slaves. The researchers demonstrate that William Wylly saw the establishment and operation of Clifton as a grand experiment in the 'proper way' to manage enslaved people. As part of his ameliorative mindset (improve slavery, rather than emancipate slaves), Wylly attempted to provide better housing stock, greater individual freedom (as expressed in free time for the slaves to tend their own provisioning grounds and to attend markets), more opportunity for religious training, and greater emphasis on literacy training than seen on many plantations.